Besides living in America, there is only one thing I have in common with Elon Musk, and that is a concern about the world’s declining birth rate. The similarities end there, as Musk and I disagree about the solutions to this conundrum. My “solution” — if I may be so bold — is to somehow make marriage great again. This will be an uphill battle for a few reasons. One is the Sexual Revolution.

In my last piece, I described what the birth control pill did to marriage, specifically through its loosening of sexual mores. This effect is ongoing — and results in single mothers being left alone to raise their unexpected children. According to Pew Research, the US has the highest rate of children living with single parents (usually mothers) in the world.

In 1960, only 5% of babies born in the US were born to unmarried women. In 2019, that number jumped to nearly half. Men and women are just not getting married in the first place. If there are children in the picture, this does not increase the chances that the parents will stay together to raise them. These statistics also explain the decrease in the rate of divorce since the 1980s; you have to get married first in order to get a divorce.

The decline in marriage rates bothers economist Melissa Kearney, who wrote a book on the subject. She notes that single-mother households are five times more likely to be impoverished than married-couple households. Concurrently, single-mother households are more likely to be non-college-educated households. In essence, marriage has become an institution reserved for the college-educated elite.

Kearney argues for marriage purely from an economic perspective. However, economic factors are working against her injunction. One is that women are giving up on men, especially non-college-educated men whose earnings have tanked since the 1980s due to (in my view) globalization and the hollowing out of the trades. These women may beget a child with such a man but eschew him as a potential spouse because they cannot rely on him financially.

To sum up, marriage is on the outs. Predictably, this decline bears directly on the children question, as three, four, and five children are only likely to occur in married households. Indeed, those who don’t have children are far less likely to have ever been married. However, as a ray of hope, in 2023, Gallup reported that a whopping 90% of Americans have kids, want kids someday, or wish they had had children.

Seemingly contradicting Gallup, The Wall Street Journal released survey results last year that showed that fewer and fewer respondents rated having children as important to them. In 1998, 59% of people claimed that having children was very important to them, while only 30% said the same thing in 2023. The story that Gallup and WSJ tell is that while many people want children in the abstract, they are prioritizing concrete, short-term gains like career, education, and money. Indeed, according to the Journal, the only value that Americans prioritize more today than they did 30 years ago is the value of the Almighty Dollar.

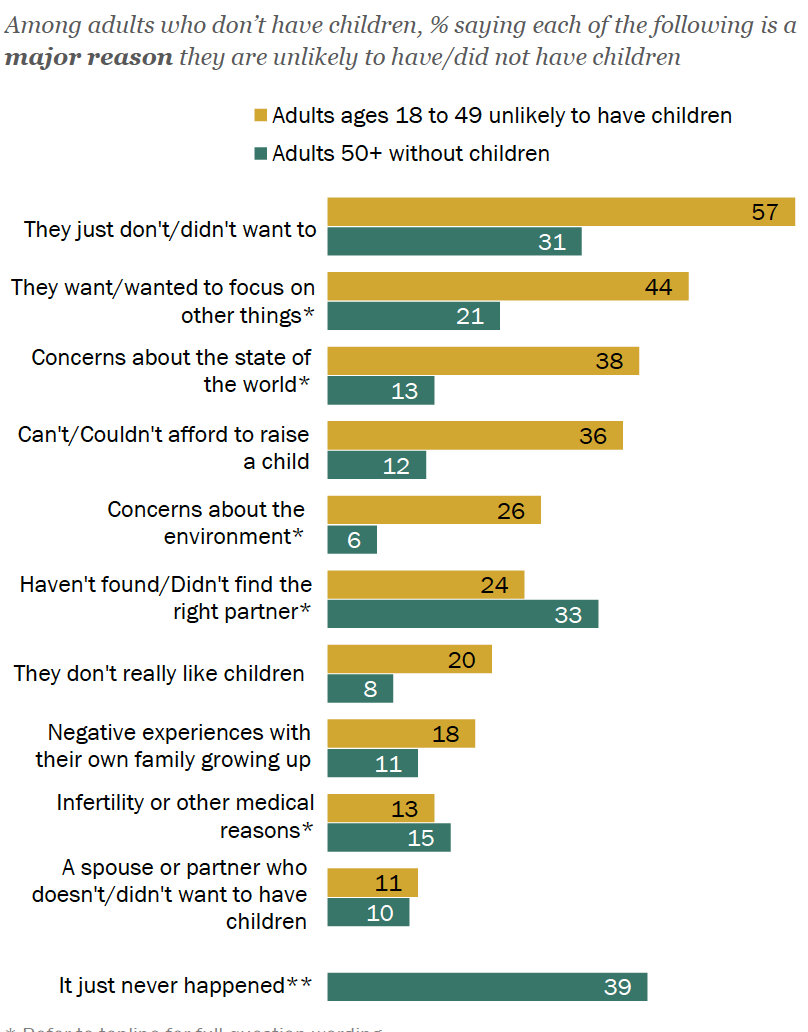

Even so, I do not think these surveys tell the whole story, and certainly not for the younger generations. When asked by Pew Research to describe their reasoning for not wanting or not having children, the majority of under 50s state that they “just don’t want to,” a non-excuse that tells us very little. External reasons they cite are wanting to focus on other things and their concerns about the state of the world, the financial costs of childrearing, and the environment.

In stark contrast, those over 50 who never had kids get closer to the truth. Sure, they may have prioritized education and career, but they really say that “it just never happened” and they couldn’t find the right partner. 33% of over-50s couldn’t find the right person, 24% of under-50s feel the same. This is the true problem — people are not finding high-quality mates and stable marriages. Other secondary issues are young people’s failure to plan for children, the prioritization of transient things, and yes, the lack of government support for families.

I am not going to be the old fuddy-duddy and claim that these folks are merely choosing to be selfish and live a lavish, dual-income lifestyle rather than do their “civic duty.” While that may be true for some, there are internal and intangible forces at play here. One of them is declining religiosity among all cohorts and subsequently, a declining sense of meaning overall.

Christine Emba notes that government support in the form of subsidies, tax credits, and paid childcare has not reversed falling birth rates anywhere, not in South Korea, Japan, or the Nordic states. The only OECD country that has a birth rate above the replacement rate is Israel, a nation that takes to heart God’s injunction to “be fruitful and multiply.” In short, this is not an economic problem, but a spiritual one.

According to Emba, women who have five or more children believe that children are not economic goods, but an “unqualified good” whose presence engenders positive meaning for the family, no matter the sacrifices necessary to raise them. Choosing to get married and choosing to become a parent are similar types of decisions: you have to dive in headfirst and believe — on faith — that the added responsibilities will be worthwhile. You have to believe that you have at least some of what it takes.

Faith, self-confidence, and moral clarity are not the hallmarks of my generation. Many in Gen Z who were raised without an overarching moral framework do not know what to make of their life. They do not know that human life is valuable in itself, more valuable than whatever they can provide to the market economy. They do not view childrearing as contributing to a better world. They do not know that God is watching out for them and that He will equip them to be spouses, mothers, and fathers.

Many Zoomers are terrified of the fortitude that life-long monogamy in marriage requires. In avoiding it, they are acknowledging that marriage demands sacrifice and that they are reticent to take on those sacrifices. To complicate things, in a post-Christian relationship, partners are forced to establish their own boundaries. Everything is up to negotiation, including the definition of adultery, openness to children, and even what to call each other. My boyfriend? My significant other? My partner?

Despite the confusion, men and women still engage in many of the trappings of marriage: they live together, share possessions, fornicate, and even have children. What is heartbreaking for all parties living in this unstable arrangement is that they have no communal or spiritual assistance to ensure their bond remains strong. What they cannot guess is this: Monogamy is impossible without the grace of God.

Monogamous, lifelong marriage without the possibility of divorce — even in the case of adultery — only became the standard after Jesus Christ proclaimed it to be so. In Jesus’ day, divorce was allowed and liberally utilized. Jesus did not make many friends when he stated that divorce was not allowed for any reason, save undisclosed, pre-marital sexual immorality. Jesus’ own followers responded, “If such is the case of a man with his wife, it is better not to marry.”

“It is better not to marry,” says the red-piller. “It is better not to marry,” says the enlightened feminist. What most young, secular people have in common is just this: they believe that Jesus’ marital ideal is too difficult to achieve. But Jesus would not have established strict boundaries around marriage if He could not have helped us rise to the challenge. With God’s grace and a leap of faith on our part, anything becomes possible, even staying true to one’s spouse and raising children in a seemingly meaningless world.

Further Reading: